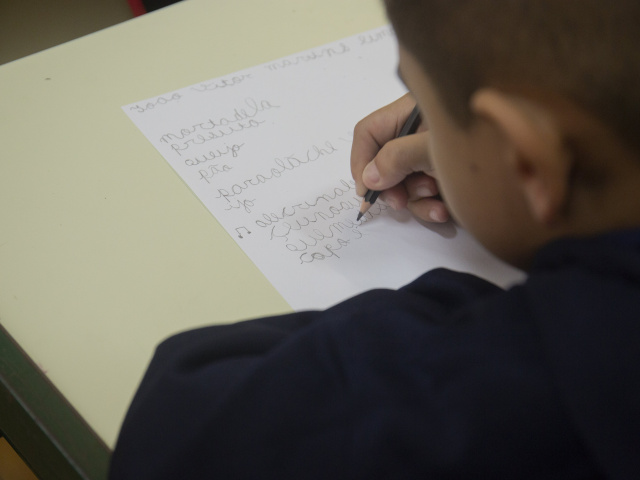

Group of students from the municipality of Moju, in Pará state, one of the cities part of Plantar Educação. Photo by: Bruna Brandão/Instituto Gesto.

Group of students from the municipality of Moju, in Pará state, one of the cities part of Plantar Educação. Photo by: Bruna Brandão/Instituto Gesto.

Environmental negligence, such as slash-and-burns and illegal mining, usually earns a spot in the media and on social media, but the guardians of the forest (guardiões da floresta) – the people who live under the treetops – remain invisible to the majority of the population. Education can be a central pillar to strengthen people’s connection with the forest and strengthen the region’s preservation. “About 80% of schools in the perimeter are outside of urban centers, within indigenous territories, or inside small riverbank communities. Half of the students learn in multigrade classrooms with children of varying ages and school years. They also do not take official education assessments, as they do not meet the minimum number of students to qualify,” detailed Kátia Schweickardt. Kátia is a professor at the Department of Social Sciences at the Federal University of Amazonas (Departamento de Ciências Sociais da Universidade Federal do Amazonas – UFAM) and creator of the Plantar Educação program, an initiative of Instituto Gesto, an organization associated with the Lemann Foundation, and supported by Porticus and the Climate and Land Use Alliance (CLUA).Giving people who live in the region a sense of belonging is one of the biggest challenges. According to the coordinator, local curricula only address the Amazon in greater depth around the 6th grade (11-to-13-year-olds), when they should have known of and had an appreciation for it since they were little. “It is common for the schools in these riverbank and forest communities to be the state’s only presence. Therefore, the connection-with-the-forest mentality needs to be emphasized to generate pro-environmental behavior in the community.” Former Municipal Secretary of Education of Manaus, capital of the state of Amazonas, and ex-Municipal Secretary of the Environment, PhD in Sociology and Anthropology, Kátia is the creator of the Plantar Educação Program, which looks at public policies in the region’s rural areas to secure an excellent education for those who take care of the forest. The initiative prioritizes education that makes sense for those living within the territory, building an Amazon curriculum.

Brazil’s last National Learning Assessment (SAEB, 2019) revealed that 31.6% of 6th to 9th grade students in the Northern region are behind in schooling. With the pandemic, the situation has declined, as the difficulties of accessing the internet have stifled school content from children and adolescents.

Plantar Educação began eight months ago and currently supports four municipalities: Manicoré and Itacoatiara, in Amazonas, and Ulianópolis and Moju, in Pará. They are vast cities with small populations. Manicoré, for example, is 48,800 km2, larger than the Netherlands, and has 57,400 inhabitants, according to a 2021 estimate (1.2 inhabitants per km2. “The program wants to reach everyone, not only in the urban centers of the municipalities, but also where there are indigenous people, quilombola descendants, and the riverbank communities. Some schools have only one person acting as the principal, the teacher, the lunch preparer, and taking care of the materials. The local reality must be recognized,” reported Kátia. The program includes addressing in class the region’s possible economic activities and its viable economic alternatives and discussing them at school so that children see that it is possible to have a dignified, sustainable life where they live. Açaí, nuts, pirarucu fishing, and bioactive extraction are a few examples of essential production chains. Tourism is a hardly explored local potential.

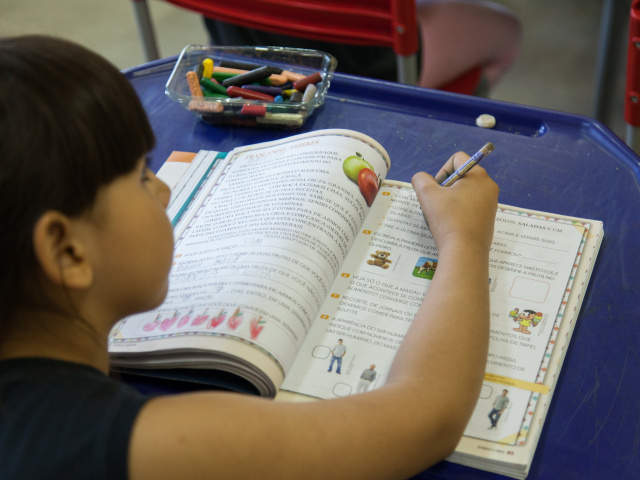

Students Hermes da Fonseca Municipal School, in Itacoatiara, Amazonas. Photo by Bruna Brandão/Instiituto Gesto.

Students Hermes da Fonseca Municipal School, in Itacoatiara, Amazonas. Photo by Bruna Brandão/Instiituto Gesto.

Strengthening education involves dialogue and connection with the forest. “The teaching materials and curricular proposals are organized with the region’s teachers and pedagogues, who often leave the classroom to teach by the river or looking at the trees. Plantar works WITH the networks and not FOR the networks,” emphasized the coordinator. The program was inspired by the successful operation of Formar, initiated at the Lemann Foundation and implemented by the Gesto Institute, which forms partnerships with municipal and state departments of education. But the Amazonian DNA is Plantar’s differential, as are its three main pillars: the strengthening of pedagogical practices, literacy at the right age, and the active search in the Amazon, where many students were left with no studies for two years during the pandemic. In September, 70 teachers and teacher-trainers from the Moju Municipal Department of Education are being trained on Teaching at the Right Level, which helps teach children of all ages to read and write.

Plantar’s short-term goal is to improve literacy, reduce age-year distortion, provide targeted training, and organize the process for networks that still do not have their own curriculum. In the future, the idea is to see a prosperous region with less deforestation and illegal mining and more economic initiatives that respect biodiversity. “Training for sustainability, one of Plantar’s pillars, will help form a generation that understands that the forest can be an asset and not an obstacle to the people’s and region’s development,” commented Denis Mizne, CEO of the Lemann Foundation.

The way of life in large cities—the consumption and exploitation of nature—affects the Amazon. According to Kátia, it is essential to convince everyone who lives in urban areas that investing in education in the region is not just a free donation, but a duty, a fair consideration for environmental services provided by those who keep the forest standing. “The region must be considered a powerful asset, and not as if it were the outskirts of the world. The Amazon has a central position and should be perceived as such. Making that light bulb go off is still our biggest challenge.”